Not only did the class have an interesting focus, but it was taught extremely well. I can say that my life has been visibly changed since taking his class. These were some of the comments that students made after taking his class on CULPA.

Professor Friedman is the best teacher I've had. He is brilliant (you may think you've had brilliant professors before but this experience will make you re-evaluate that), intellectually rigorous (what do you say about a teacher who is able to tie all the tangents together), challenging (you WON'T find anyone who thinks like him and he expects you to think for yourself as well) and compassionate (really listens to students and seems to care). I have also never taken a class with such devastating intellectual and political implications.

He made people feel self-conscious about the quality of their comments in class. But, I will be forever grateful that I took this class because I got over my fear of public speaking and it really opened my mind and challenged me to think constantly during the class. He comes off as opinionated, but I think that's just because he knows he's right :). He really took the discussion to places I have never before nor since traveled to in any other class here. Always challenging us NOT to assume things, not to be lazy in thinking liberal ideology is always right, to read critically - to have our "bullshit detector" always on.

He's simply mind-blowing, funny, and the smartest person I've ever met (and that's genius level, because I like to think I'm pretty smart myself!). His democracy class was the best class I've taken at BC-- the readings on public ignorance and human fallibility were so compelling that I can no longer read the NY Times in the same complacent way I used to. Really, he should write a book and change the world.

After his class, it has been has almost been impossible to find worthy reading material on the NY Times ... until now.

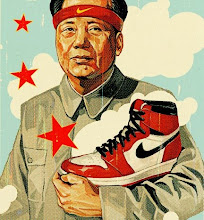

Going through all of the NY Times daily emails that I had forgotten about during the Olympics, I found an amazing article entitled Harmony and the Dream written by op-ed columnist, David Brooks. It describes the basic difference between individualistic and collective societies (exactly like my liberalism and communitarian class) under the auspice of the 2008 Olympics in Beijing where the idea of friends living in harmony was a central theme during the Games.

The world can be divided in many ways — rich and poor, democratic and authoritarian — but one of the most striking is the divide between the societies with an individualist mentality and the ones with a collectivist mentality.

This is a divide that goes deeper than economics into the way people perceive the world. If you show an American an image of a fish tank, the American will usually describe the biggest fish in the tank and what it is doing. If you ask a Chinese person to describe a fish tank, the Chinese will usually describe the context in which the fish swim.

These sorts of experiments have been done over and over again, and the results reveal the same underlying pattern. Americans usually see individuals; Chinese and other Asians see contexts.

This concept translates further than just the Olympics. It is embodied in politics, business, society and even personal friendships. It is the small, yet overarching difference between the East and West. And I believe it is the key for mutual understanding between the different worlds.

David Brooks should continue this train of thought and help Americans and the western world examine and reexamine its view of China. There is much more to be written and seen.

Here is the full text of the article:

The world can be divided in many ways — rich and poor, democratic and authoritarian — but one of the most striking is the divide between the societies with an individualist mentality and the ones with a collectivist mentality.

This is a divide that goes deeper than economics into the way people perceive the world. If you show an American an image of a fish tank, the American will usually describe the biggest fish in the tank and what it is doing. If you ask a Chinese person to describe a fish tank, the Chinese will usually describe the context in which the fish swim.

These sorts of experiments have been done over and over again, and the results reveal the same underlying pattern. Americans usually see individuals; Chinese and other Asians see contexts.

When the psychologist Richard Nisbett showed Americans individual pictures of a chicken, a cow and hay and asked the subjects to pick out the two that go together, the Americans would usually pick out the chicken and the cow. They’re both animals. Most Asian people, on the other hand, would pick out the cow and the hay, since cows depend on hay. Americans are more likely to see categories. Asians are more likely to see relationships.

You can create a global continuum with the most individualistic societies — like the United States or Britain — on one end, and the most collectivist societies — like China or Japan — on the other.

The individualistic countries tend to put rights and privacy first. People in these societies tend to overvalue their own skills and overestimate their own importance to any group effort. People in collective societies tend to value harmony and duty. They tend to underestimate their own skills and are more self-effacing when describing their contributions to group efforts.

Researchers argue about why certain cultures have become more individualistic than others. Some say that Western cultures draw their values from ancient Greece, with its emphasis on individual heroism, while other cultures draw on more on tribal philosophies. Recently, some scientists have theorized that it all goes back to microbes. Collectivist societies tend to pop up in parts of the world, especially around the equator, with plenty of disease-causing microbes. In such an environment, you’d want to shun outsiders, who might bring strange diseases, and enforce a certain conformity over eating rituals and social behavior.

Either way, individualistic societies have tended to do better economically. We in the West have a narrative that involves the development of individual reason and conscience during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, and then the subsequent flourishing of capitalism. According to this narrative, societies get more individualistic as they develop.

But what happens if collectivist societies snap out of their economic stagnation? What happens if collectivist societies, especially those in Asia, rise economically and come to rival the West? A new sort of global conversation develops.

The opening ceremony in Beijing was a statement in that conversation. It was part of China’s assertion that development doesn’t come only through Western, liberal means, but also through Eastern and collective ones.

The ceremony drew from China’s long history, but surely the most striking features were the images of thousands of Chinese moving as one — drumming as one, dancing as one, sprinting on precise formations without ever stumbling or colliding. We’ve seen displays of mass conformity before, but this was collectivism of the present — a high-tech vision of the harmonious society performed in the context of China’s miraculous growth.

If Asia’s success reopens the debate between individualism and collectivism (which seemed closed after the cold war), then it’s unlikely that the forces of individualism will sweep the field or even gain an edge.

For one thing, there are relatively few individualistic societies on earth. For another, the essence of a lot of the latest scientific research is that the Western idea of individual choice is an illusion and the Chinese are right to put first emphasis on social contexts.

Scientists have delighted to show that so-called rational choice is shaped by a whole range of subconscious influences, like emotional contagions and priming effects (people who think of a professor before taking a test do better than people who think of a criminal). Meanwhile, human brains turn out to be extremely permeable (they naturally mimic the neural firings of people around them). Relationships are the key to happiness. People who live in the densest social networks tend to flourish, while people who live with few social bonds are much more prone to depression and suicide.

The rise of China isn’t only an economic event. It’s a cultural one. The ideal of a harmonious collective may turn out to be as attractive as the ideal of the American Dream.

It’s certainly a useful ideology for aspiring autocrats.

7 comments:

great blog man

Unfortunately I'm not sure it's an economically rigorous argument that David Brooks makes. I think it takes a certain ideological bent to take his position that only just barely understands "the other side".

I understand the appeal that collectivism has. Who doesn't think that having strong social networks is a good thing? But let's also look at the societies with collectivism that tend to be ethnically homogeneous - and as an unfortunate corollary, tend not to be as open to outsiders. Even China - as you know what they call outsiders, demons that they are. Japan is an excellent example. I wonder how he would explain the development of HK that the British governed in a state of "benign neglect".

The system of economics has much to do with it, and unfortunately I suspect here too David Brooks has a very poor understanding of why and how markets work where collectivism fails.

Interestingly, Silk Road's blog makes the following criticism of Friedman's recent column:

"The sad thing is not that China held an honestly great event or took the most golds but that Thomas Friedman (NYT, The World is Flat) and others are jealous of the Chinese govt’s ability to “get things done.” They whine about the fact that in democracies projects can’t move as fast (due to unions, human rights, legal statutes, contractual obligations and other worthless democratic bullshit). They think that infrastructure and events are more important than people and freedom. Pathetic really."

The idea that individualism is a western ideal is in itself a bit of a fairy tale - and while one can see the great harmony that it takes to orchestrate what was the tremendous feat of a successful Olympics, the flip side is to see a great deal of oppression in order to do so. Collectivism further, only really works in theory. You've had experience at factories, and if you thought that level of harmony was because of an injection of market realism, I can't seem to find the link right now but there's a site that transcribed some of the diaries of those who worked at communist factories.

Seeking to understand economics is acknowledging that people respond to incentives - and further, understanding that not all incentives are financially based. Brooks deeply misunderstands what economics is. Further, to ascribe China's rise to the rise of collectivism is just humorous and completely devoid of historical context.

Incidentally, more rigorous critiques here of Brooks' column:

www.chinaeconomicreview.com/editors/2008/08/15/bloviating-on-the-olympics-give-china-a-break/

and here:

http://news.imagethief.com/blogs/china/archive/2008/08/12/olympic-match-up-brooks-vs-fallows.aspx

This point of this post isn't to argue an economic issue. It's to discuss the basic difference between the East and West - a liberal vs. communitarian comparison. I see that you (and many others in the world) don't see the implications and ramifications of this.

Most westerners are trapped by their own inherent beliefs and ideology. Because they have liberal ideology, they write with that as the foundation. The reason why I posted this article and hope that Brooks writes more on this issue is that this basic foundation is a huge gap between east and west.

Within the silk road quote you cited this ideology is already apparent: "They think that infrastructure and events are more important than people and freedom. Pathetic really."

The Silk Road believes in people and freedom as most important. That's the liberal view. As Brooks says: The individualistic countries tend to put rights and privacy first. People in collective societies tend to value harmony and duty.

This is the same as you using the word "oppression" in your statement. Oppression of RIGHTS. Again, i refer you to Brooks...The individualistic countries tend to put rights and privacy first.

Other comments:

Japanese are 鬼子 because (as everyone can agree) there's a past there. Chinese people are more racist and "we think we're better than you" than not-open.

China has forever been an entrepreneurial and creative society - not just after the capitalist reforms under Deng Xiaoping. Lets not forget who invented gun powder, paper, the compass and printing. China's recent success in the world market also proves this. This success has been on the backs of collectivism.

Economics is a reflection of core values and beliefs and I think that's what you're not understanding in my argument here. It's also a core weakness of those who don't quite understand the utility of economics.

It doesn't depend on individualism or collectivism. However you would be correct that inherently if the collective were to suppress individual needs then it would change the dynamic of the markets but is inherently stifling.

Within China right now, the idea that the wealth creation has been the result of a resurgence of collectivism is somewhat muted by the reality on the ground. To paraphrase: to become rich is glorious. History repeats in the process of development and to compare the thinking of those today with even a hundred years ago within Western societies you might get similar realms of thinking particularly when you look at Edward Bellamy's highly popular book that inspired those like Marx to Engels to Hitler.

As even Imagethief points out who says is generally sympathetic to Brooks, the gross generalities are ludicrous and beyond which if you look at the economic review article it's quite the hop step and a jump from making some rather simplistic views of word/picture associations to collectivism.

Incidentally to take the opposite view to the Silk Road perspective is to agree with ideas like this - http://time-blog.com/china_blog/2008/08/olympic_controversy_update_jai.html?xid=rss-china (I'd make the argument this isn't about collectivism/socialism but being human?); not to mention the fact that it is difficult to get away from the reality that collectivist societies tend to also be a lot more corrupt by their nature which is a significant impediment for growth - think animal farm: all people equal but some a lot more equal than others.

Oppression is not just about individual rights either - but it is about oppressing ideas and even large swaths of communities in the name of the collective (which history shows is often really about maintaining the power of a select few).

The irony is that much of the innovations stopped in China when it went more collectivist and looked inwards. But back to the point made about economics - economics just shows what we value in what we consume versus what we say so it is a far better reflection of who we are. And in this, it is the reemergence of individualism rather than an inherent collectivism that is at the root of the recent economic strength. Western civilization is also not without its collectivist scholars but I tend to ascribe it to the survival of the fittest (which is admittedly liberal) as far as ideas go that have resulted in those like Engels and Marx (Germans) being relegated to the trash heaps of history.

Folks may want to remember that it's not Brooks' idea, originally ...

How Asians & Westerners Think Differently

ya i agree to u

Post a Comment